Art and Water III: The One Who Brought Water to the Tap

A journey through the infrastructures and technologies that led to the water revolution and its reflection in the world of art.

Infrastructures and scientific and technological advances led to a revolution in the relationship between citizens and water in terms of well-being and health. New ways of capturing, pumping, channelling and treating water made this possible. Let’s see.

Well (extraction)

The development of new extraction techniques such as steam pumping and, later, electrical energy facilitated the capture of water from subsoil aquifers. This was a transformative element that marked a before and after in urban life.

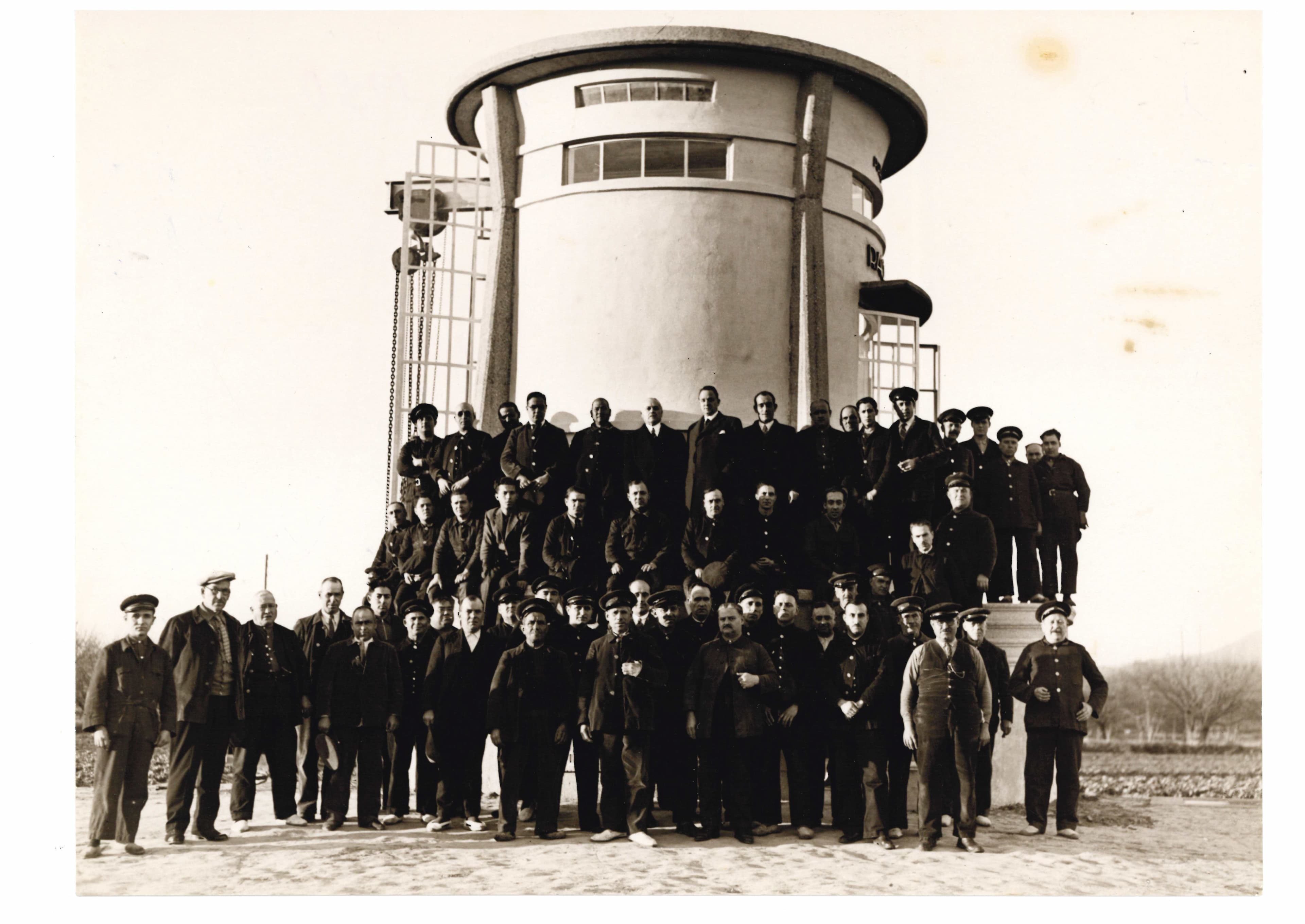

Through this photograph we can clothe the history of Barcelona’s water supply with a human face. Jackets and plate caps characterized the uniforms of SGAB workers for many decades.

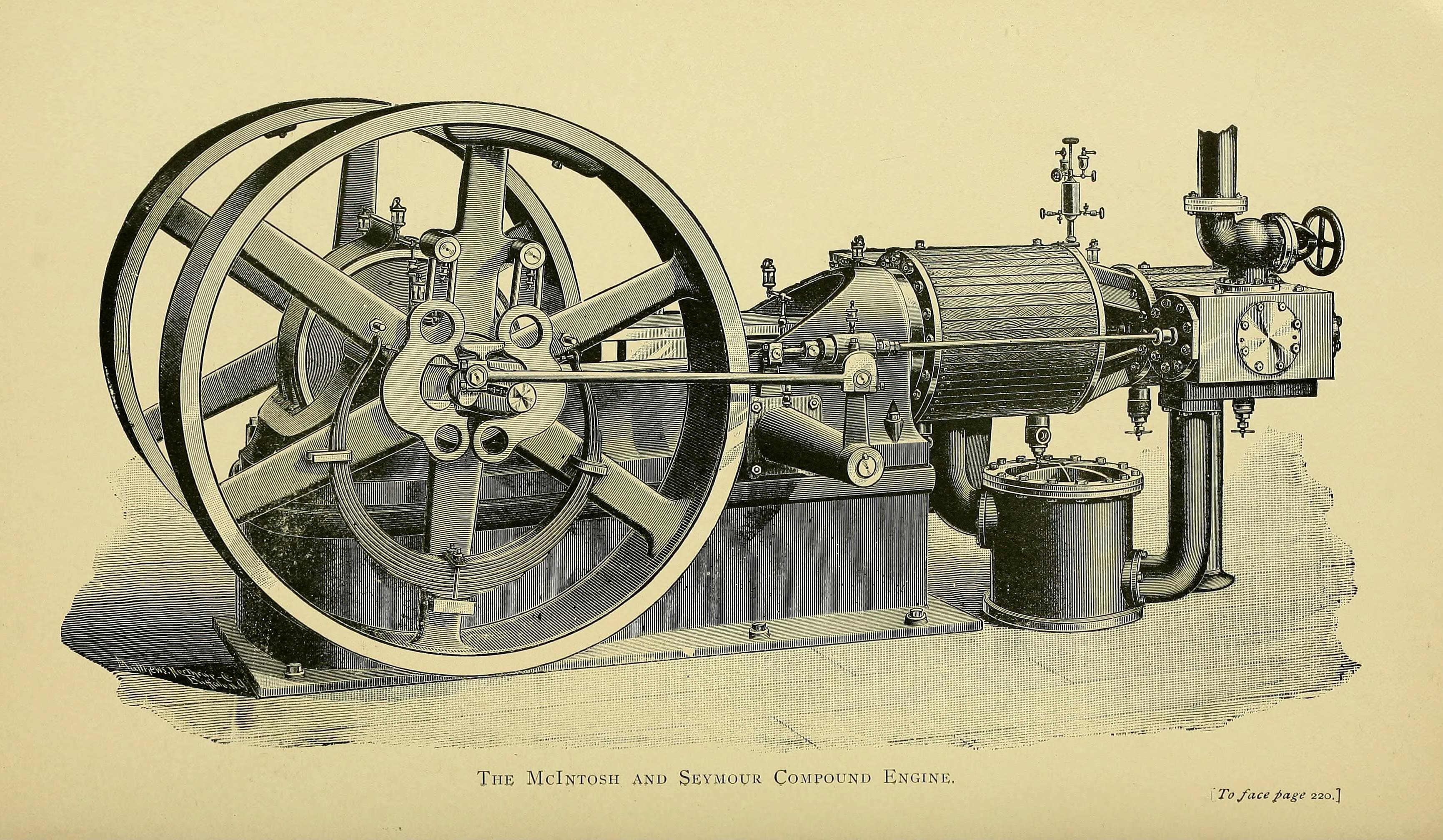

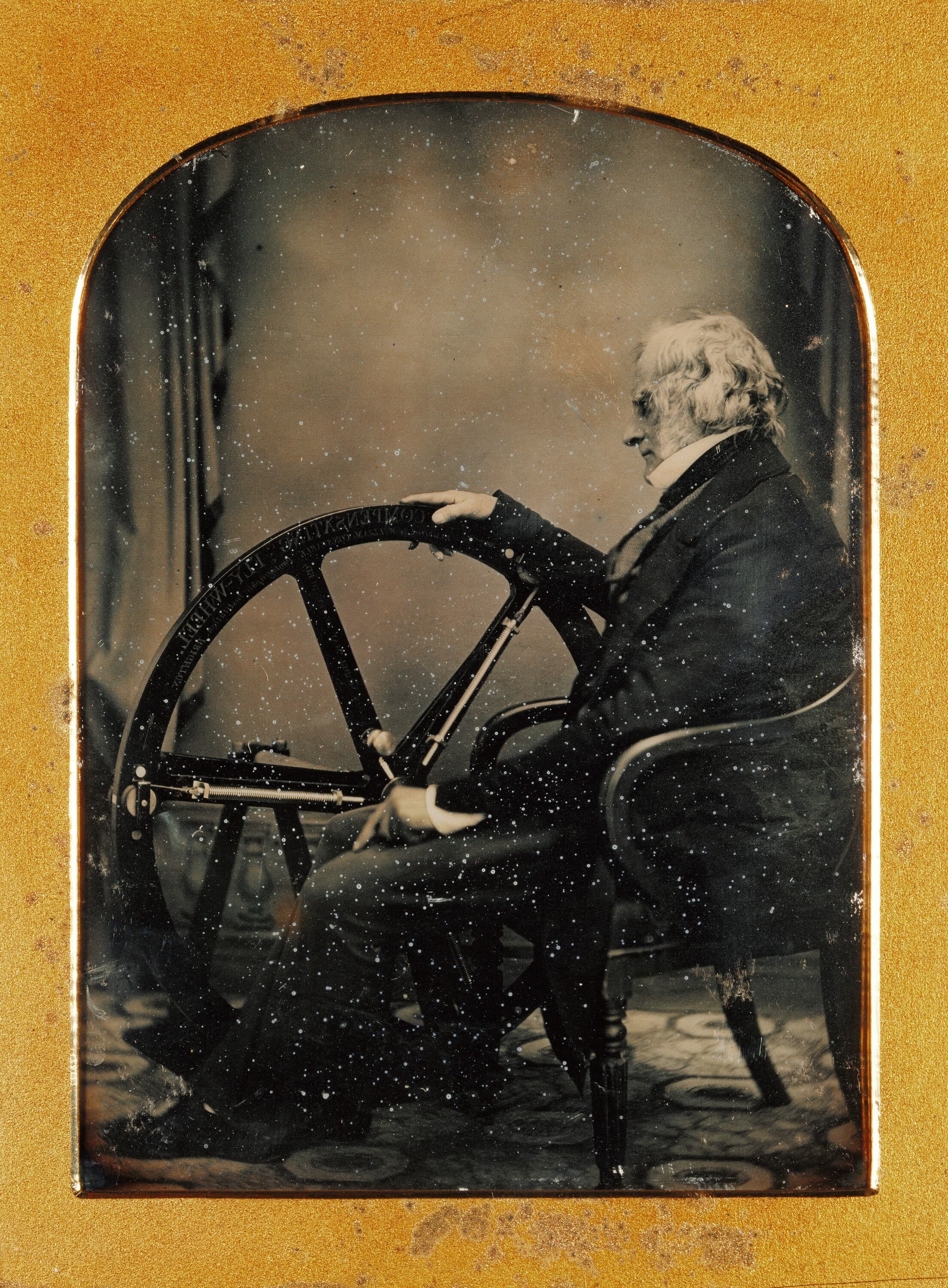

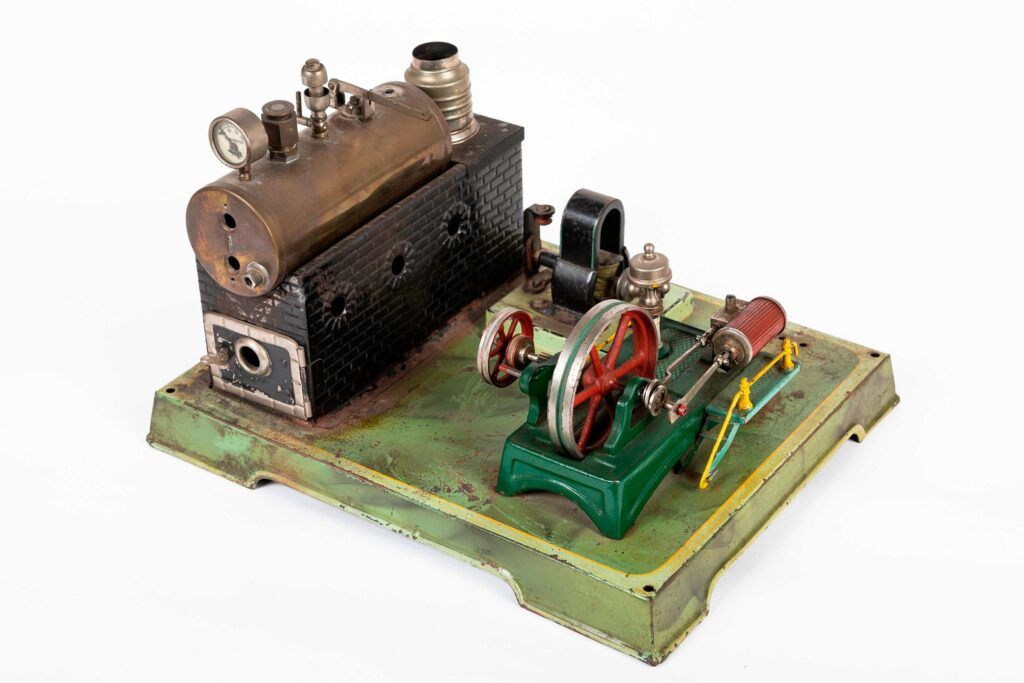

Generator

Thanks to modern generators such as this one, it was possible to convert the force of the steam produced in the boilers into electricity, necessary for pumping the water from the wells.

William Constable (1783-1861) shows himself in this daguerreotype, in which he presents his latest invention to regulate the force of steam. His peculiar position in profile, covering part of the machine, denotes a claim of pride as its creator.

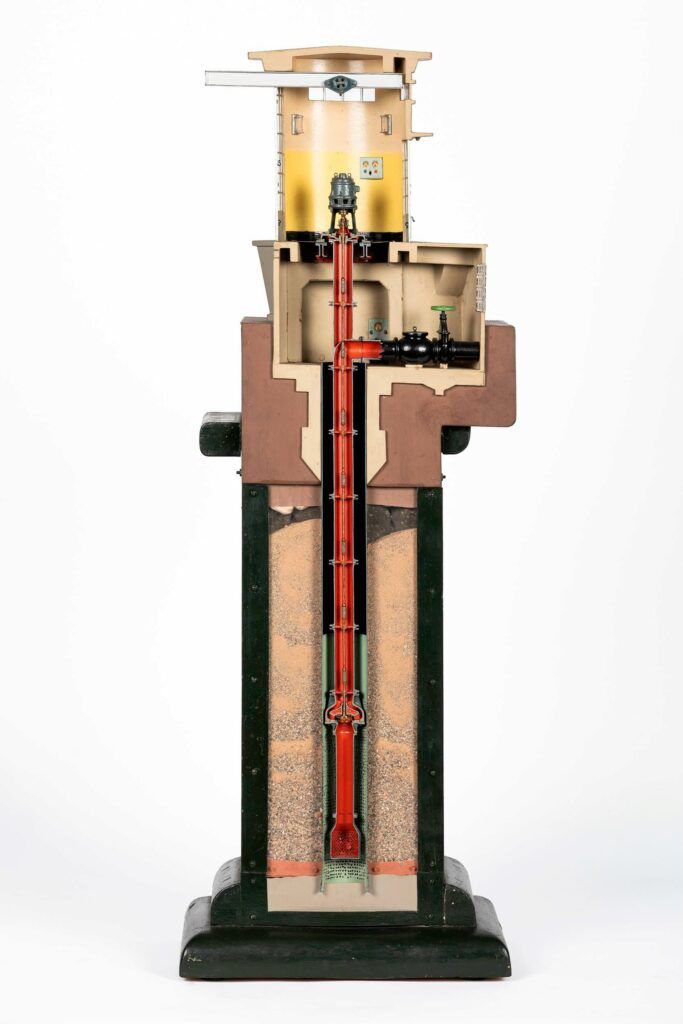

Water Lift Pump

Lifting pumps were indispensable for pushing and distributing water throughout the network, especially to high points where it could not reach by itself with the force of gravity alone.

In this period engraving you can see a pump feeding a fountain in an industrial exhibition, typical of the last half of the nineteenth century. In it, the pump is claimed as an innovation.

The taste for scientific and technological advances became a new form of leisure for the refined bourgeoisie.

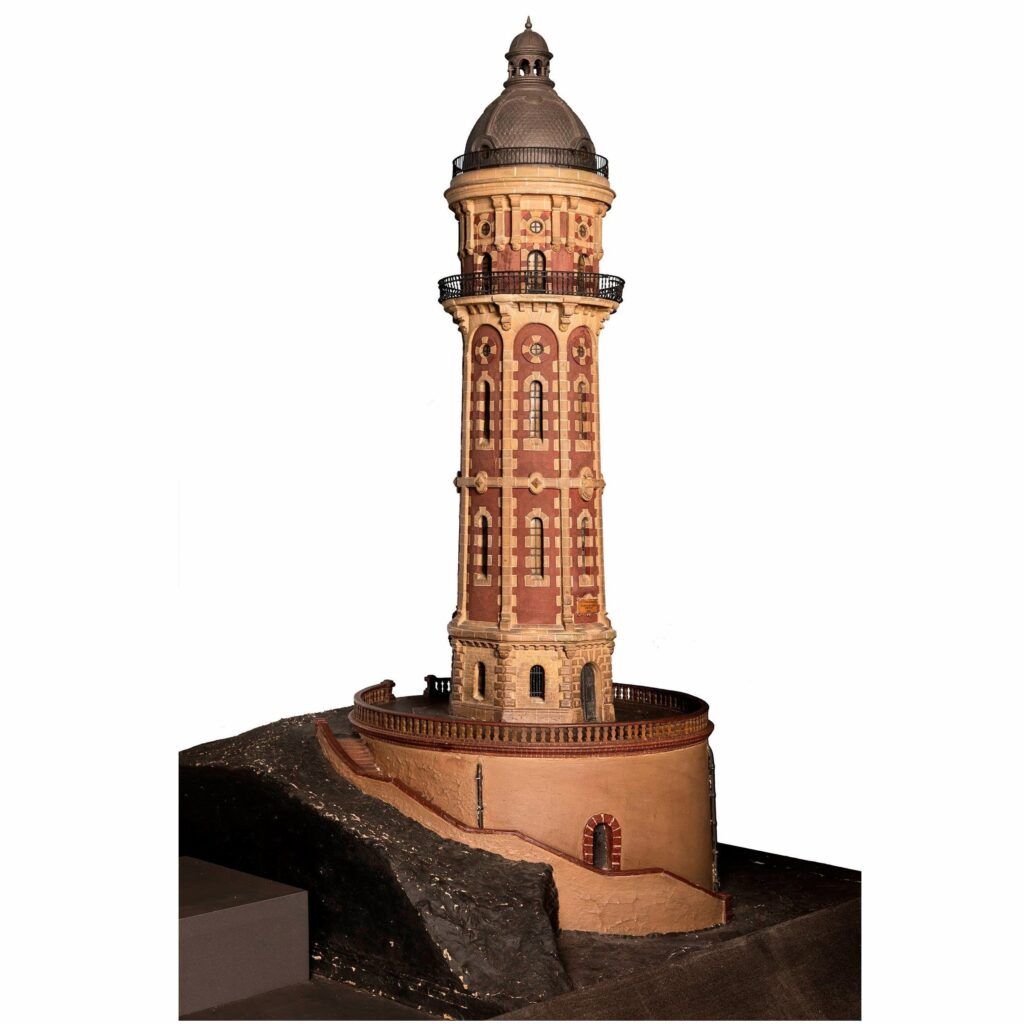

Elevated tank (Torreó)

From elevated tanks such as the Torre de les Aigües de Dos Rius, in Tibidabo (Barcelona), the water descended by the force of gravity to the homes, thus guaranteeing the necessary pressure.

The Torre de Dos Rius appears in the pictorial collection “Lugares de Barcelona” (2020) by Ernest Descals, where the artist reflects the most unique attractions of the city.

Tubes

To bring water to homes, it was necessary to build kilometers of network using resistant and durable materials. A large part of the history of Barcelona’s water takes place inside the “Bonna” pipes, like the one in the image, made of steel coated with reinforced concrete.

The sculpture by Paulí Collado stands on the Josep Tarradellas square in Cornellà. A forged steel butterfly, the artist’s specialty technique, rests on a large water channeling pipe.

The Bonna tube was commemoratively deposited in the same place where the factory that gave it its name once stood, demolished in 1979. Thus, this large tube becomes both a work of art and a place of memory.

Quality Control

Quality control was decisive for the elimination of impurities that for centuries had transmitted diseases through water. Constant analysis of samples made it possible to weave a sanitized network, free of infectious agents.

Albert Edelfelt, with a style influenced by Impressionism, depicts Louis Pasteur in his laboratory on Rue Ulm (Paris). The scene evokes the greatness of Pasteur and scientific knowledge.

Thanks to advances in bioscience such as those of Pasteur, at the end of the nineteenth century the theory of miasmas as the origin of infectious epidemics was refuted and the focus was on microorganisms.

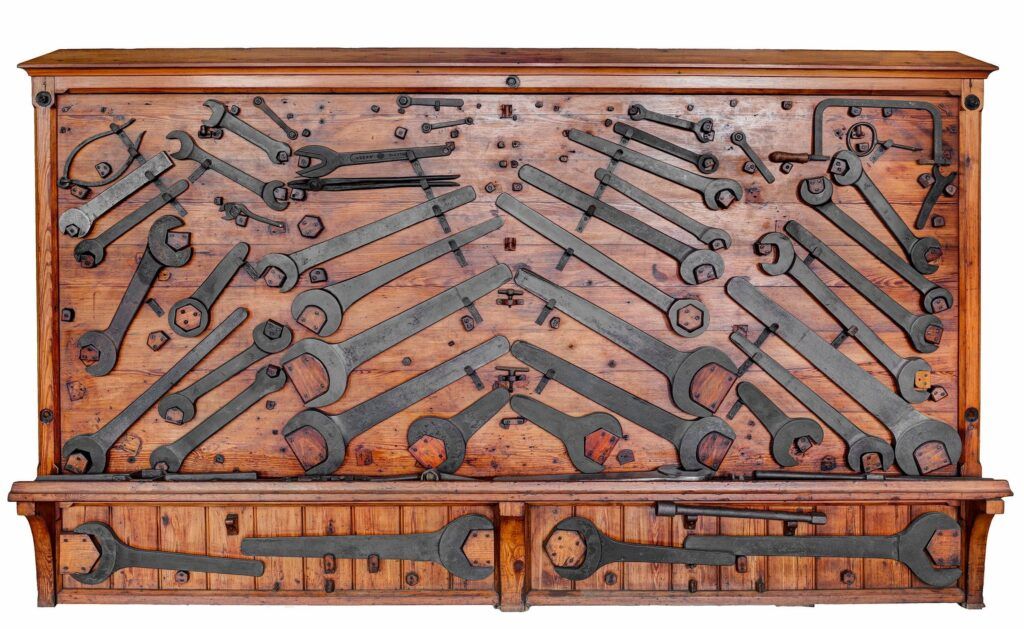

Maintenance

Complete toolboxes like this allowed the correct performance of the maintenance tasks of the machines and boilers. Daily maintenance has been key to the proper functioning of the network that brings water to our home.

The American photographer Lewis W. Hine presents with this 1921 image a fusion between sociological photography and art. It is a photographic piece with a documentary intention about the industrial working class, but with an undeniable artistic intention.