Art and Water I: Before Tap Water

A walk through history through objects and works of art that show what life was like before the arrival of water in homes.

The objects exhibited at the Museu de les Aigües come to life in the work of great artists and tell us about the times when it was still necessary to go and find water outside the houses.

The pulley

Before water reached the taps of homes, it was necessary to fetch it from public fountains or wells, which were only available in some houses. The pulley reduced the effort to be made to extract the water thanks to the change in direction of the applied force.

The painter Santiago Rusiñol (1861-1931), based on the uses and customs of his contemporaries, was a visual witness to the importance of water, both for practical daily uses, and for setting the typical interior courtyards of the nineteenth century with vegetation.

In his well-known painting The Blue Courtyard, he reproduces in detail the most elementary pulley, used to well the water.

The hand pump

The need to reduce the effort to obtain water led to technical innovations that facilitated this task, based on a set of pressures. The first bomb dates from the third century BC.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905), a prominent French painter, naturalist and romantic, shows us a young woman, sitting next to a hand pump, with the expression of poetic shyness typical of bucolic painting.

As the title of the work evokes, the girl’s displeasure is due to the fact that the pitcher has broken, depriving her of the longed-for water.

The pitcher

This is probably one of the oldest known water containers. Its primitive form has evolved and crossed eras and continents, without losing its high degree of effectiveness in maintaining fresh water.

In The Harvest of Malvasia, Joaquim de Miró i Argenter (1849-1914) clearly emphasises the use of the pitcher as an essential element in agricultural work until well into the twentieth century.

The ferrata

The ferrata, a typical object of grazing crops (sheep, goats) and cattle farming, is used as a container to contain and transport water, milk and other liquids.

The method of transport can be seen in the advertising poster by Josep Morell i Macias (1899-1949) Woman with ferrata on her head and granary in the background, where various Galician ethnographic elements are represented with the aim of promoting tourism.

The ferrata is stable on the protagonist’s head.

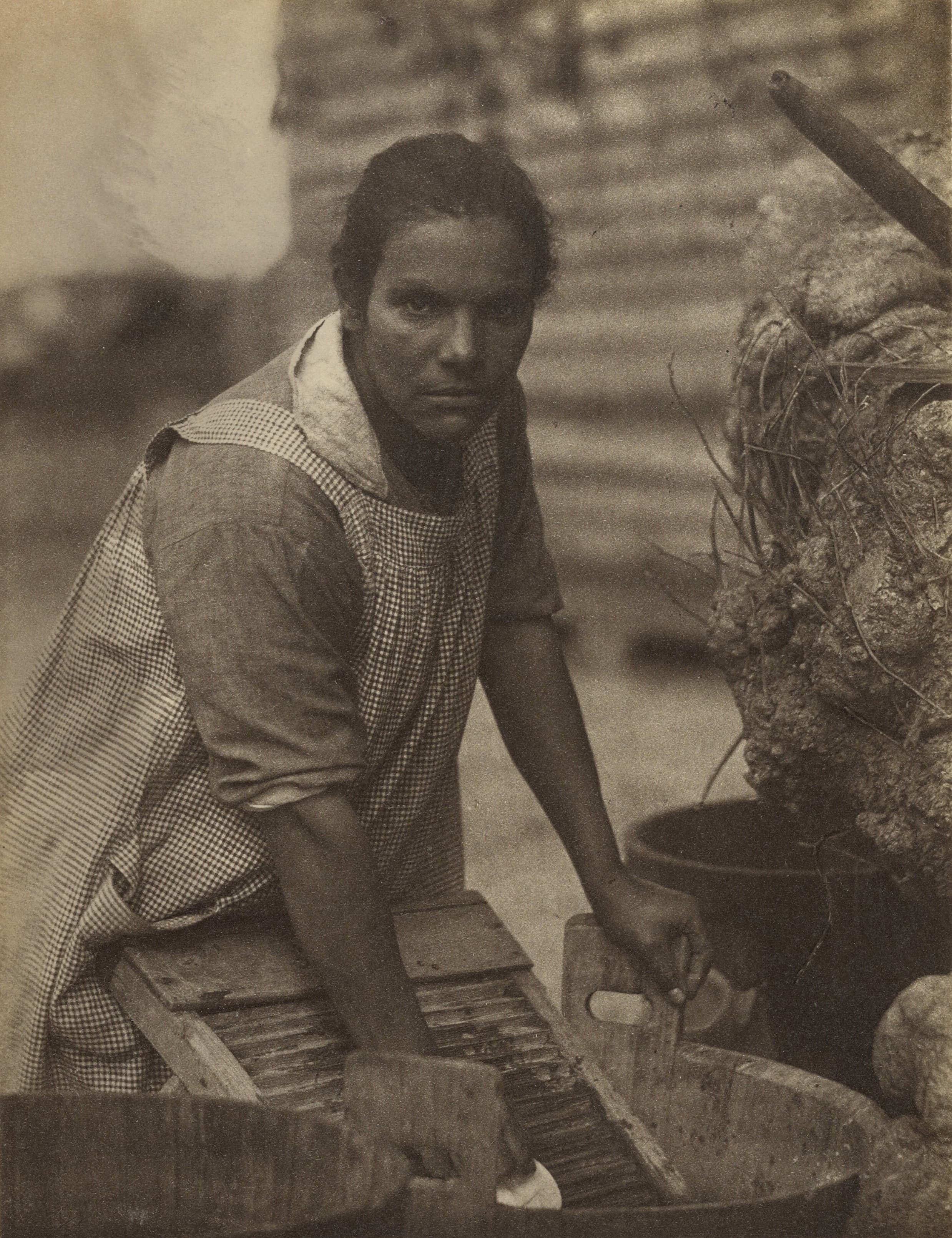

Washing wood

The cleaning of household clothes made it necessary to go to public spaces where the washing table was a basic utensil. The wood made the work easier, as it was possible to lean on.

In this pictorialist photograph, elements that are not at all accidental such as the facial expression and the twisted torso of the woman, produce a strong visual impact and perfectly synthesize the hardness and intensity of manual washing of clothes.

Sink and jug

The concepts of cleanliness and hygiene through water underwent a fundamental transformation at the end of the nineteenth century. A household element as common as the sink, present in many of the rooms intended for bedrooms, will be lost with the arrival of tap water.

A bedroom that is as austere as it is colourful will give Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) the opportunity to almost inventory the essential elements for a single room at the end of the nineteenth century.

The painter incorporates the sink and the jug as vital minimums, in his well-known pictorial work Bedroom in Arles.

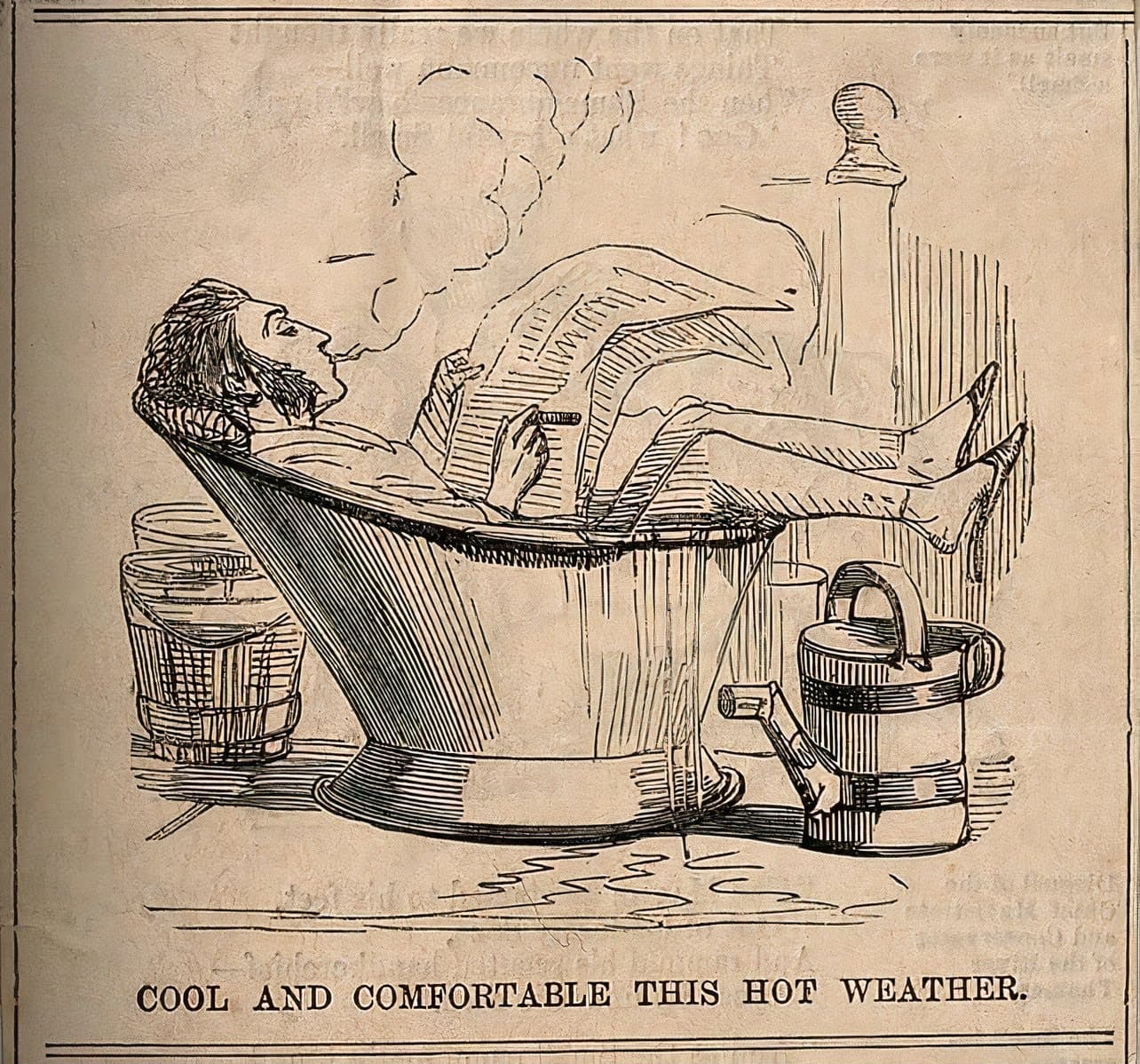

Seat bathtub

Until well into the twentieth century, the bath was mainly used for therapeutic purposes. The appearance of new containers promised new uses of water, such as the cure and relief of pain or, simply, a pleasant rest.

This newspaper illustration depicts a bourgeois character comfortably seated, smoking and reading the press in a bathtub, as a caricature of the British bourgeoisie.

The cossi

The cossi appears in most houses. Due to the robustness of its structure, its apparently simple function became essential in washing, draining, transporting and hanging clothes.

In the mid-1880s, Edgar Degas (1834-1917) painted a series of seven pastels with the same motif, that of a woman collecting water with a sponge during personal cleansing, in a wide and shallow body.